In the flat, green heart of the Mekong Delta, known as Kampuchea-Krom (កម្ពុជាក្រោម) in the Khmer language, a quiet yet powerful struggle endures. There are no battles or soldiers here, only Buddhist monks, children, and the sacred sound of their mother tongue being taught in temples. The Khmer- Krom people continue their journey to preserve their language and identity.

For centuries, the Khmer-Krom have lived in this region long before borders were drawn. During the French colonial period, the Mekong Delta was known as French Cochinchina, and Khmer-Krom children were still allowed to study in Franco-Khmer schools. They could read and write in their mother tongue. Their identity, despite the harshness of colonialism, still had space to breathe.

That changed when the Vietnamese communist regime came to power in 1975. Khmer-Krom children were no longer allowed to learn their language in public schools. Textbooks in Khmer disappeared. The teaching of their own history became forbidden, even Buddhist monks, who had long served as teachers and cultural guardians, found their lessons monitored and restricted.

Yet, against this silence, the sound of the Khmer language refused to fade.

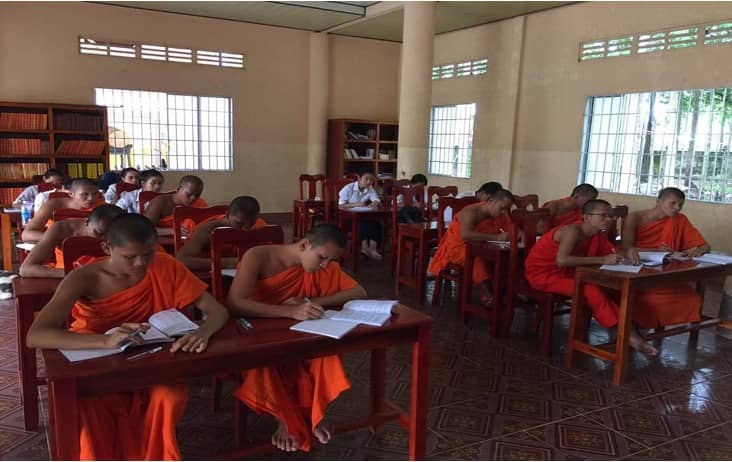

In small villages scattered across the Mekong Delta, the temples, or known in Khmer as Wat (វត្ត), became the last sanctuaries of the Khmer-Krom language. Inside these sacred spaces, barefoot children gathered after school or at dawn, learning to trace the graceful curves of Khmer script on chalkboards under the guidance of monks. These Buddhist monks, often young themselves, risked punishment and surveillance to preserve their heritage. Their mission was simple but powerful: to ensure that future generations would still know who they are.

The Vietnamese government’s control extended even into the temples. Authorities forbade monks from teaching the true history of Khmer or from running independent schools. But despite the constant monitoring and intimidation, the monks continued. For them, teaching their language was not just an act of education, but also an act of resistance, a spiritual duty to protect the soul of their people.

In 2004, the Khmers Kampuchea-Krom Federation (KKF) brought this issue to the global stage by attending the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) in New York for the first time. KKF’s representatives spoke courageously about how the Khmer-Krom were being denied the right to learn their language. Vietnam’s government responded by accusing KKF of spreading false information. But KKF did not back down. Year after year, the organization continued to raise the issue before the UN and international human rights bodies.

Eventually, under international attention, Vietnam began allowing limited Khmer-language classes in some public schools, usually just two or three hours per week. It was a small step forward, but not enough for students to master their mother tongue. And when Buddhist monks peacefully demanded broader rights to teach Khmer and practice their faith freely, the government reacted with repression. In 2013, Khmer-Krom Buddhist monks such as Venerable Ly Chanh Da, Venerable Lieu Ny, and Venerable Thach Thuol were arrested and imprisoned solely for peacefully advocating for their people’s cultural and linguistic rights. A decade later, repression continues. Venerable Thach Chanh Da Ra, Venerable Duong Khai, Venerable Kim Som Rinh, and other Khmer-Krom monks have been targeted for their efforts to preserve the Khmer language within their temples and to educate their communities about their indigenous rights as recognized in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). For this peaceful work, they have faced reprisals, with several sentenced to prison terms ranging from three to six years.

Their courage became a symbol for the entire Khmer-Krom community, and for Indigenous peoples everywhere who struggle to protect their heritage from erasure.

Thanks to their sacrifices and continued advocacy from KKF, Khmer-Krom communities now have slightly more freedom to learn and teach their language within temples. Children still gather there after school, or during the summer break, reciting prayers and learning letters from monks who remain steadfast despite ongoing restrictions. The classroom walls may be worn, and resources scarce, but the spirit is unbroken.

The Khmer-Krom story is one of quiet resilience. In every temple where a Buddhist monk teaches the Khmer script, and in every child who learns to write their name in their ancestral language, lives the strength of a people refusing to disappear. For the Khmer-Krom, who face assimilation on their ancestral lands, language is more than just words; it is a memory, an identity, and a dignity. As long as these devoted monks continue to teach, the voice of the Khmer-Krom will endure, and their spirit will never be silenced.